The 6 different stages of clay

Clay is a fascinating (and sometimes frustrating!) substance. It has completely different properties at different stages throughout its drying and firing cycle. In this blog post we explore the 6 main stages of clay, the properties and uses of each one.

The 6 essential stages of clay (from wettest to driest)

1. ) Slip

Slip is clay with added water to make it into a paste or liquid.

Use: Slip is most commonly used to join pieces of wet or leather hard clay together. It can also be used decoratively. Colour can be added to slip to make a decorating medium which can be painted on to wet or leather hard clay or applied in lines with a pipette (‘slip trailed’). Slip can also be mixed with chemicals to make it extra runny and used with a plaster mould to cast pieces of pottery in a process known as ‘slip casting’.

2.) Wet clay

Wet clay is used by many Potters to produce their work. It usually comes in 12.5kg plastic bags from pottery suppliers who make the clay up using different combinations of rocks and clays. It must be kept wrapped in plastic at this stage to keep it in a usable state.

Use: Wet clay can be used to make an infinite array of pieces using many different techniques. It can be used to throw pots on the wheel, roll out flat slabs, to clay shapes cut out with cookie cutters, pull handles, impress marks in or hand build sculptures.

3.) Leather-hard clay

When wet clay has dried slightly but is not fully dry it is known as ‘leather-hard’.

Use: Leather-hard is a useful clay state, because the clay is strong but still wet enough to be shaped. Pots thrown on the wheel are now strong enough to have their bases ‘turned’ where the pot is turned upside-down the foot ring is carved whilst on the wheel. Leather-hard is often the state when flat slabs of clay are joined together to make 3D structures.

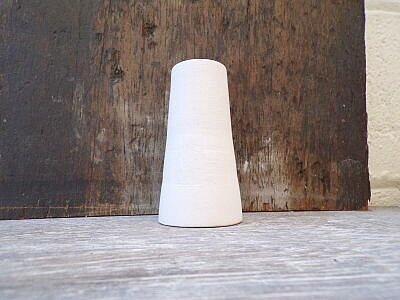

4.) Dry clay

Dry clay is also known as ‘greenware’. It is when clay is at its most fragile, and needs careful handling to prevent breakages. Dry clay needs to be fired in the kiln in order to make it strong enough to use.

Use: Any sharp edges that are not smoothed at this stage will become solid in the bisque firing. Final finishing of work is done with a damp sponge.

5.) Bisque

‘Bisque’ refers to clay which has been fired once. For stoneware clay this firing reaches temperatures of 950oc which permanently changes the chemical and physical nature of the clay. Clay at this stage is hard but still porous enough to absorb glaze.

Use: This is the stage at which glaze is applied ready for the final firing. Work can be dipped into glaze or glaze can be poured over the bisque pot. Water is absorbed into the clay making the glaze stick to the surface of the pot.

6.) Glaze ware

After a second firing to 1260oc for stoneware clay, the clay and glaze have fused making a non porous surface. Hopefully the firing has resulted in an evenly melted glaze which has not run too much (sticking the pot to the kiln shelf!).

Use: This is the final, finished stage, although sand paper can be used to smooth any remaining sharp edges. Ideally there should be no glaze faults such as ‘crazing’ when the glaze cracks or ‘shivering’ when the glaze flakes and peels away from the clay.

So these are the 6 stages of clay. A lot of the time in pottery is spent learning about what you can and can’t do with your particular type of clay at each stage.

Different clays have different properties, ‘porcelain’ for example is made of 50-60% china clay and very smooth whereas ‘crank’ has added grit or grog (fired clay ground into a rough powder), for strength and texture. It is only by practising and trying things out with your type of clay that you learn its limitations and possibilities.